2000 - the ARC (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers)

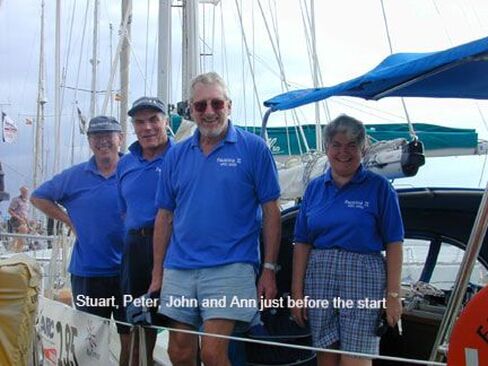

The crew

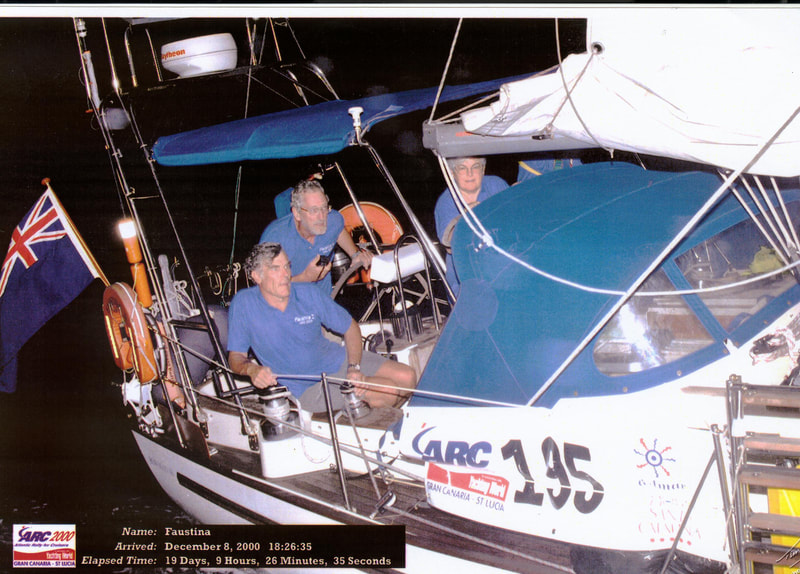

The crew for the ARC was to be John and Ann (owners) together with Peter Ronaldson, a fellow member of the Irish Cruising Club and a past Commodore who owns his own cruiser, and Stuart Osborne, who has done some sailing and is a radio expert.

The crew

The crew for the ARC was to be John and Ann (owners) together with Peter Ronaldson, a fellow member of the Irish Cruising Club and a past Commodore who owns his own cruiser, and Stuart Osborne, who has done some sailing and is a radio expert.

Preparations in Las Palmas, Canary Islands

It was a hectic week that led up the start of the ARC on Sunday 19 Nov. Although we had bought lots of tinned food with us from NI we still had to buy and load fresh food for an expected 3 week+ voyage. We did most of our shopping at El Cortes Ingles, a wonderful and very helpful supermarket that offered free deliveries to the boat. What a help!

Cardboard boxes were not allowed on board and everything was washed to ensure that no cockroaches (or roaches as the Americans call them) came with us. We were successful in that endeavour! The labels were removed from tins and their contents marked with permanent ink. We hung all the fresh fruit in a net in the main cabin where it caused no bother, or on deck under the boom, whilst the vegetables were stored in three laundry baskets in the forward cabin. In accordance with tradition we hung our branches of bananas in the cockpit – and later ate them well before they became too ripe.

With help from Stuart, Ann made a stowage list to show where everything had been packed away.

It was a hectic week that led up the start of the ARC on Sunday 19 Nov. Although we had bought lots of tinned food with us from NI we still had to buy and load fresh food for an expected 3 week+ voyage. We did most of our shopping at El Cortes Ingles, a wonderful and very helpful supermarket that offered free deliveries to the boat. What a help!

Cardboard boxes were not allowed on board and everything was washed to ensure that no cockroaches (or roaches as the Americans call them) came with us. We were successful in that endeavour! The labels were removed from tins and their contents marked with permanent ink. We hung all the fresh fruit in a net in the main cabin where it caused no bother, or on deck under the boom, whilst the vegetables were stored in three laundry baskets in the forward cabin. In accordance with tradition we hung our branches of bananas in the cockpit – and later ate them well before they became too ripe.

With help from Stuart, Ann made a stowage list to show where everything had been packed away.

We attended numerous parties and seminars - the later on subjects ranging on everything from ‘cooking on board’ to ‘astro navigation’. A splendid German did much work on our antenna to rectify the poor performance of our SSB radio (which was never as good as we had hoped). Charles Mauder of Bowman Yachts arranged to have a partition added to our fridge which greatly improved the way it worked and, above all, we had the services of Giles and Gilliam, experts from B&G, for two days to repair (successfully) out B&G autopilot – free of charge. The start day rushed towards us.

It became apparent that Peter had a fairly mild case of shingles and so we found some Chicken Pox pills in case I caught it too. I never did.

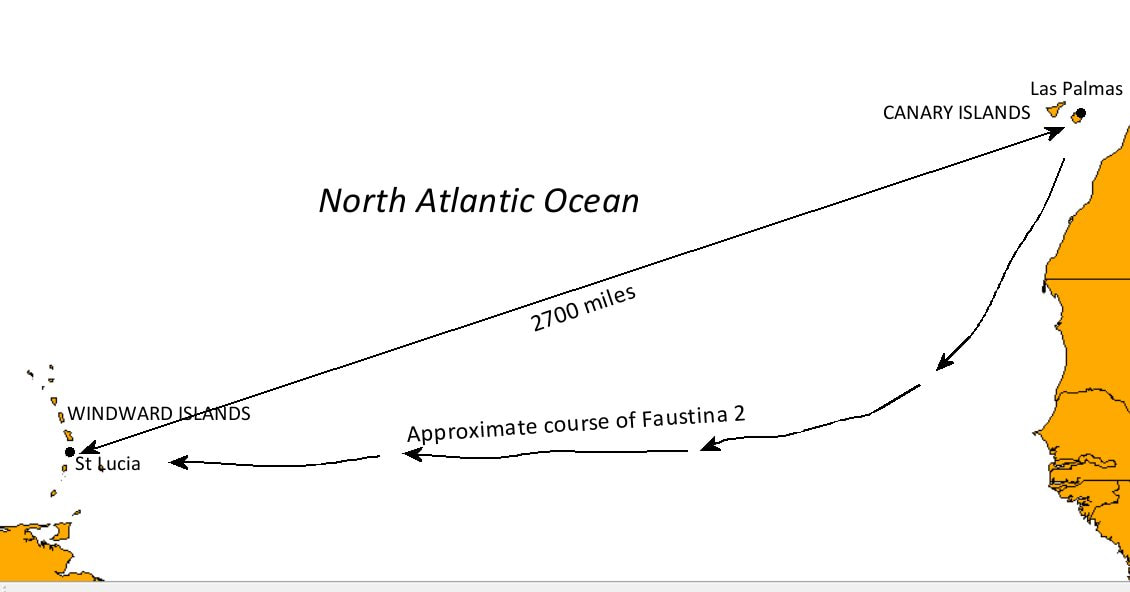

The crossing to St Lucia is about 2700 miles and we hoped to complete in between 18–22 days (although we had food and stores enough for 30 days.)

The Atlantic Voyage

The start of the ARC was at 1300 on 19th November 2000 We tried to hold back from the crowd of some 220 other boats at the start on the basis that there was no real rush – we were not racing - but a lot of others had the same idea and the ‘second wave’ of starters was probably greater than the first! However, we were off at last in some N'ly fresh wind and bouncy seas. Later that evening, after dark, the wind died and we flopped around a lot. Not fun and very wearing.

The crossing to St Lucia is about 2700 miles and we hoped to complete in between 18–22 days (although we had food and stores enough for 30 days.)

The Atlantic Voyage

The start of the ARC was at 1300 on 19th November 2000 We tried to hold back from the crowd of some 220 other boats at the start on the basis that there was no real rush – we were not racing - but a lot of others had the same idea and the ‘second wave’ of starters was probably greater than the first! However, we were off at last in some N'ly fresh wind and bouncy seas. Later that evening, after dark, the wind died and we flopped around a lot. Not fun and very wearing.

We set an initial course to take us well to the south in order to find the Trade Winds as soon as possible. We held this course for three days during which we had a mixture of strong and fluky winds. It was all a bit wearing as the boat flopped about quite a lot. Then on Thu 23 Nov we at last found ourselves in the steady easterly winds that we wanted and we altered course to WSW and were soon bowling along in grand style. This is what we had come for!

By now the rest of the fleet were out of sight and we began to realise what a very large ocean we were crossing. The days became warmer and the sky has small fluffy clouds that indicate the presence of the Trades. It was usually wonderful sailing but occasionally the easterly wind would rise to Force 6 from its more usual 4 or 5 and then the waves would get up to 10 to 12 feet. However, they were always benign and caused no problems. F2 behaved immaculately throughout.

Really the only down side of sailing at these latitudes was that the nights were as long as the days. 12 hours of dark seemed rather long when there wasn’t much to do. However, the stars were amazing as we were looking at them with no light pollution at all. For most of the voyage we had Venus brightly ahead and Saturn astern with Orion providing a fine display overhead. (For the most part we sailed at night with a single masthead light that shown red, green and white as required.)

One night I was taking over the watch from Peter. We decided to reduce sail a bit before he went off to bed. Normally we didn’t need any light on deck as the light from the stars and the moon provided all the light that we needed to move around the deck that we knew so well. However, there was a sudden scuffling noise in the cockpit. Concerned, I grabbed a torch and found a flying fish in the scuppers. As I went to get rid of it overboard it managed to shuffle along to one of the drain pipes that lead straight down to the sea, pushed aside the plastic ball covering it and dropped through into the seat. It was all so unexpected that we laughed enough to wake up Ann who was sleeping just below. We had many flying fish aboard every morning which had to be cleared off and returned to the water.

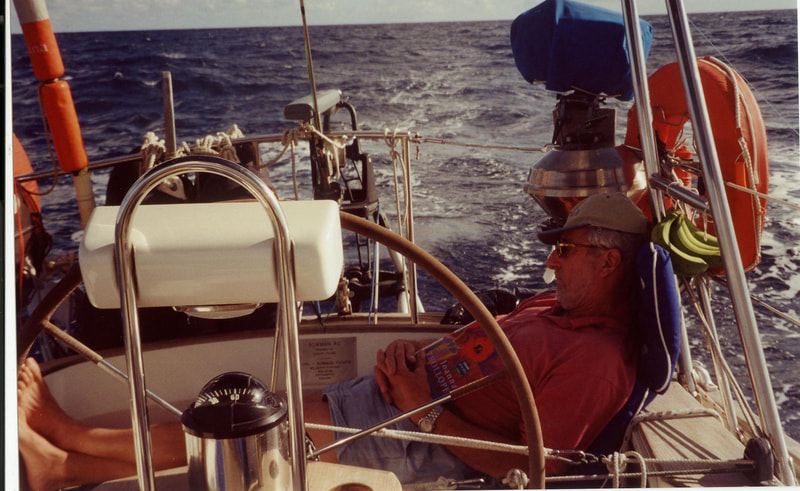

Our watch routine worked very well. Ann stood no watches - unless she volunteered a daytime watch - but in return she did all the cooking. As a bonus the aft cabin was given over for her exclusive use. If she was asleep and anyone was hungry there was always a goodies bag’ of sweets, nuts etc. that was replenished as necessary. The other three crew stood 3-hour watches at night and 4-hour watches during the daylight. That meant that every night everyone got different hours on duty. During the 1800-2100 watch we took our evening meal (after last light) – having reduced sail to what was considered prudent for the night hours ahead, The ‘pain’ was alleviated by a Happy Hour at 1800 - which stretched to a Happy Two Hours on the four occasions when the clocks were put back an hour. Generally, we made our own breakfasts.

Our sail plan was simple. The mainsail stayed up throughout and we devised an easily deployed preventer to stop an inadvertent gybe. I had decided not to bring a big Genoa with us and so forward, the No 3 genoa was alternated with the Cruising Chute depending on the wind strength. We never flew the Cruising Chute (or ‘Shouting Chute’ as Ann called it – I wonder why?!) at night. Indeed, Ann would not serve the evening meal until it was down!

Our sail plan was simple. The mainsail stayed up throughout and we devised an easily deployed preventer to stop an inadvertent gybe. I had decided not to bring a big Genoa with us and so forward, the No 3 genoa was alternated with the Cruising Chute depending on the wind strength. We never flew the Cruising Chute (or ‘Shouting Chute’ as Ann called it – I wonder why?!) at night. Indeed, Ann would not serve the evening meal until it was down!

During the day we read, ate, and fished. There was usually some boat maintenance to be done. We daily checked the rigging, sails and engine and the whole deck area was inspected. One day we found two bolts on the foredeck and discovered that the genoa roller reefing had shed them. These had to be replaced before we could roll on the sail. We also found that the gooseneck on the boom had a bit of a wobble and we put a rope around it ‘just in case’. It held and was only replaced several months later in Trinidad. Our GPS made navigating very easy and a bit of daily chart plotting usually resulted in an instruction such as, ‘We’ll gybe tomorrow – or the day after’!

Fishing – we had attached a large game fish reel to the goal post behind the cockpit. None of us knew anything about fishing but I had brought some line and lures from El Cortes Ingles in Las Palmas. Our ‘secret weapon’ was Percy the Prawn, a greeny/pink plastic squid about 4 inches long. This we trailed 100m behind us when the mood moved us to do so – and we had almost too much success. Our first catch was a Yellow Jack that provided us with 8 steaks and some filets. We later caught smaller ones of these and a good sized tuna. We also caught a barracuda about 2 foot long which we decided that we did NOT want. It gave Stuart a good bite on his (fortunately) gloved hand before it was released. The catches were a useful addition to our fresh diet.

We saw occasional wild life – though strangely, no birds at all. An unidentified whale passed 200m ahead of us apparently quite unperturbed by our presence. One day six 30ft long Minke whales accompanied us for about an hour. They behaved rather like lumbering dolphins, seeming to treat the boat as an amusement. One came right alongside and slid then under the boat and up the other side. TG it didn’t touch us!

Another day we were accompanied by literally hundreds of dolphins. Looking down from the bow the sea was solid with them hustling to get in to the bow wave. They could be seen on either side of the boat for several hundred metres. We played Tina Turner loudly to them on the cockpit speakers and they seemed to share the skipper’s taste for the raunchy music.

The days slipped by without any boredom. We had taken on the task from the ARC people of being a ‘net controller’. Every other day we called up the 65 yachts in our ‘slower boats’ group on the SSB radio to obtain their position and urgent/interesting news, and the weather in their area. Those without SSBs sent their message to a nearby SSB equipped boat by VHF radio which would relay it to us during our ‘schedule’. We would start the calls by giving them the special ARC weather forecast that we received from the UK on our Inmarsat-C satellite receiver. Once we had received all the position data, we would send it to ARC HQ in UK by Sat-C where it was put onto the ARC website for relatives and friends to see. This all worked quite well for us and gave the voyage a certain rhythm. Towards the end of the voyage we had some trouble connecting with some boats as they were stretched out over 600 miles behind us. We used the VHF to talk to some boats just over the horizon and to other boats that would occasionally come near us. We saw no commercial traffic at all.

Another day we were accompanied by literally hundreds of dolphins. Looking down from the bow the sea was solid with them hustling to get in to the bow wave. They could be seen on either side of the boat for several hundred metres. We played Tina Turner loudly to them on the cockpit speakers and they seemed to share the skipper’s taste for the raunchy music.

The days slipped by without any boredom. We had taken on the task from the ARC people of being a ‘net controller’. Every other day we called up the 65 yachts in our ‘slower boats’ group on the SSB radio to obtain their position and urgent/interesting news, and the weather in their area. Those without SSBs sent their message to a nearby SSB equipped boat by VHF radio which would relay it to us during our ‘schedule’. We would start the calls by giving them the special ARC weather forecast that we received from the UK on our Inmarsat-C satellite receiver. Once we had received all the position data, we would send it to ARC HQ in UK by Sat-C where it was put onto the ARC website for relatives and friends to see. This all worked quite well for us and gave the voyage a certain rhythm. Towards the end of the voyage we had some trouble connecting with some boats as they were stretched out over 600 miles behind us. We used the VHF to talk to some boats just over the horizon and to other boats that would occasionally come near us. We saw no commercial traffic at all.

Electrical power on a modern sailing boat equipped with electronics etc is constantly in demand- especially in warm climates. Not only is the fridge having to work harder but the nights are longer. I thought that we had adequate battery storage and charging capacity. She has 3 x 120 AHr batteries (one of which was reserved for starting the engine) and a 20 AHr alternator working off the engine. We also have a solar panel, a wind generator and a water generator that we trailed across the Atlantic (though not much since.) Despite all these I never felt that the batteries were being fully charged. In Trinidad I took professional advice and fitting a battery and charging monitor This was a real eye-opener because it was clear that we had never got the batteries up to full charge. We later fitted a smart charger which controlled and optimised the charging supplied. A cruising boat cannot have too much power available.(Much later again I fitted 4 deep discharge service batteries and a small battery for the engine starting.)

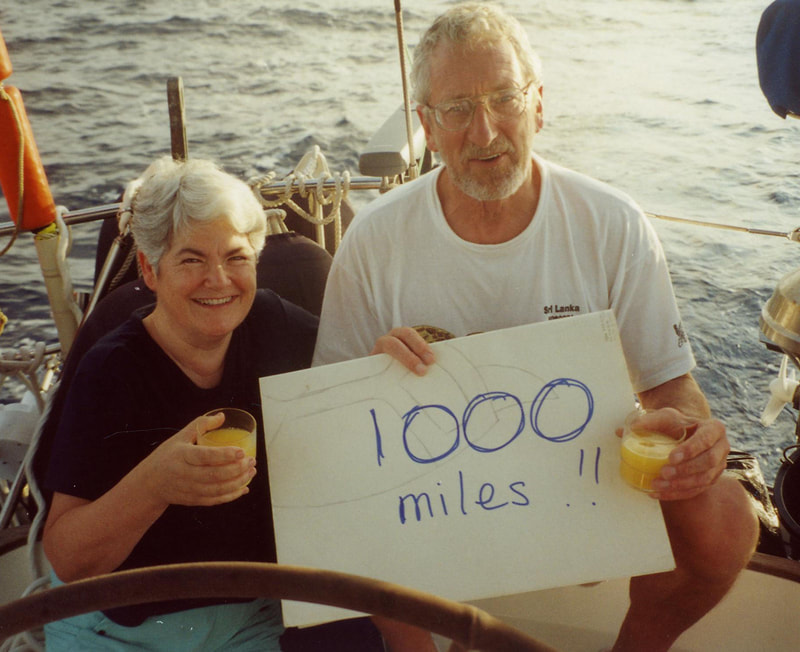

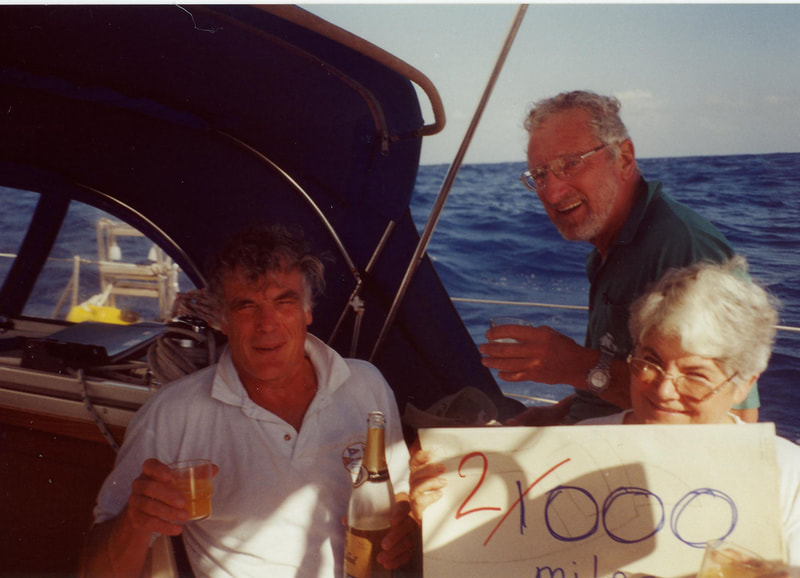

Our average daily run was 140 miles and it rarely varied more than about 10 miles either way after the first few days. We used the engine every day to charge the battery and very occasionally to propel the boat during periods of very light wind.

Our average daily run was 140 miles and it rarely varied more than about 10 miles either way after the first few days. We used the engine every day to charge the battery and very occasionally to propel the boat during periods of very light wind.

St Lucia appeared over the horizon as the sun set

Ann’s birthday was on 8 Dec and the men decided to decorate the boat’s interior with bunting and to waken her with breakfast in bed (made by Stuart) and served with Buck's Fizz.. She did no cooking all day. It was also a momentous day for the voyage as latte that afternoon St Lucia hove into sight. We had made excellent progress over the last three days. Flushed with the speed that we were making, we held the Cruising Chute flying until the last moment as we reached the waypoint off the north end of the island - and managed to do a massive broach during which Peter lost his favourite hat and Stuart his spectacles – all overboard. It was entirely the skipper’s fault.

Later, in the dark, we rounded Pigeon Island and, for the first time since leaving Las Palmas, headed into the wind to finish off Rodney Bay marina. We crossed the line in 19 days, 9 hours and 26 minutes – a time that we were well pleased with- an average of 5.8 knots.

Ann’s birthday was on 8 Dec and the men decided to decorate the boat’s interior with bunting and to waken her with breakfast in bed (made by Stuart) and served with Buck's Fizz.. She did no cooking all day. It was also a momentous day for the voyage as latte that afternoon St Lucia hove into sight. We had made excellent progress over the last three days. Flushed with the speed that we were making, we held the Cruising Chute flying until the last moment as we reached the waypoint off the north end of the island - and managed to do a massive broach during which Peter lost his favourite hat and Stuart his spectacles – all overboard. It was entirely the skipper’s fault.

Later, in the dark, we rounded Pigeon Island and, for the first time since leaving Las Palmas, headed into the wind to finish off Rodney Bay marina. We crossed the line in 19 days, 9 hours and 26 minutes – a time that we were well pleased with- an average of 5.8 knots.

We reach St Lucia

We made our way cautiously into the marina – not knowing quite where we were to moor. Once settled we were greeted with a gift from the ARC reps of a bottle of rum and a basket of local fruit. Evie, Peter’s wife was also there, clutch yet another bottle of rum. We had a great party on board before going out to a local ‘Jump-Up’ That was the night that I fell in love with the music of the steel bands – or ‘pan’ music as it is known in the WI. It was a long and memorable evening!

We made our way cautiously into the marina – not knowing quite where we were to moor. Once settled we were greeted with a gift from the ARC reps of a bottle of rum and a basket of local fruit. Evie, Peter’s wife was also there, clutch yet another bottle of rum. We had a great party on board before going out to a local ‘Jump-Up’ That was the night that I fell in love with the music of the steel bands – or ‘pan’ music as it is known in the WI. It was a long and memorable evening!

Rodney Bay marina on St Lucia